Planetary System Types for Traveller

When doing Jump Destinations, I try to give every mainworld on the map some unique features, including embedding said mainworld in its own unique sytem.

Judging from UWPs, a typical Traveller star system consists of one sun, one mainworld (presumably the most hospitable/populated/import-ant world insystem), with optional Gas Giant(s) (for fuel-skimming) and/or asteroid belt(s) (for Belters).

Actual star systems are a bit more complex than this, including double/multiple stars, secondary worlds (which could also be places of interest) and special features in a variety of arrangements. To avoid “If it’s Tuesday, this must be Vulcan” monotony, a decent Traveller campaign should include a wide variety of systems.

Glossary

AU (Astronomical Unit): Earth-Sun Distance, the main unit of measure for planetary systems. Approximately 150,000,000 km.

Earth-equivalent distance: The distance from its sun where a planet receives the same solar energy as Earth. Distance (in AU) = square root of star’s luminosity (in Sols [1 Sol is the luminosity of Earth’s sun]).

Frost Line: The distance where volatiles remain solid (ices) and Gas Giants can form. Inside the Frost Line, solid planets and moons will be rockballs; outside, iceballs. Usually considered to be about 4.85×Earth-equivalent distance.

Habitable Zone: The range of orbits where liquid water can exist on-surface. Sometimes called ‘Goldilocks Orbits’; usually considered to be 0.9 to 1.5×Earth-equivalent distance.

Orbit (capitalized) or Traveller Orbit: Traveller nomenclature, an artifact of Book 6: Scouts where planetary orbits are in numbered zones based on the spacing of Sol System.

“-bis Orbit”: Expansion of Traveller nomenclature; Orbits intermediate between the whole-number Traveller Orbits. From “System Generation/Adaptation from ACCRETE”, Freelance Traveller #78, Nov/Dec 2016.

Torch Orbit: Ultra-close star-grazing orbit with an orbital period (year) of only a few days at most; the planet’s bright face will be red-hot. For Traveller purposes, inside an arbitrary boundary of around 0.25×Earth-equivalent distance (16×Earth’s solar flux). In Sol System, Orbit 1 (Mercury) is not a torch orbit, but Orbit 0 (hypothetical Vulcan) would be.

Single-star Systems

The majority of main-sequence stars are single; the ratio of binaries/multiples goes up as the stars go up the mass/spectrum.

A Sol-type System is composed of well-spaced small Rockballs out to the Frost Line, Gas Giants beyond. Originally called a “Conventional System” until the discovery of a large number of exosystems showed Sol to be a very unconventional system.

The system generation process in Book 6: Scouts is optimized to generate this type of system.

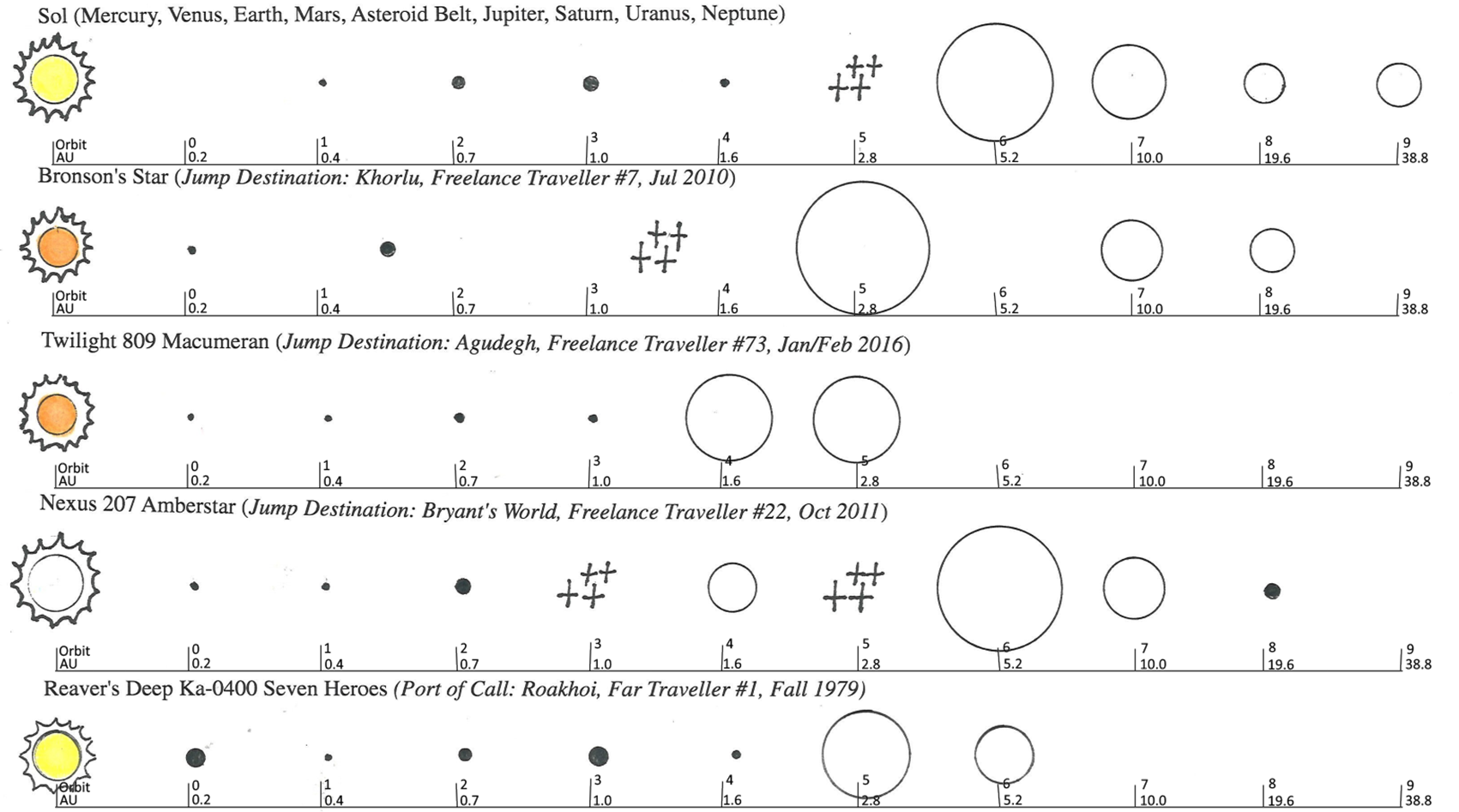

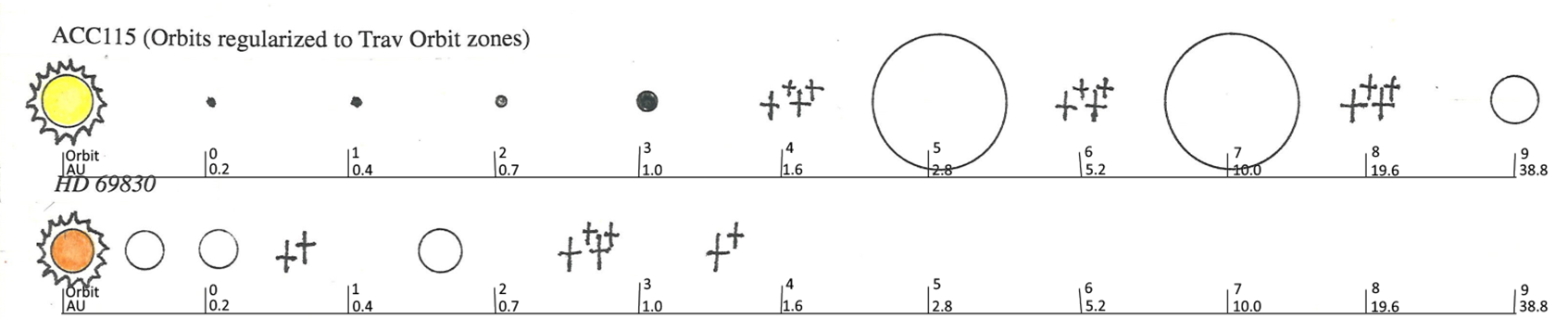

Figure 1: Sol-type Systems

An ACCRETE-type System is a variant of Sol-type System generated by running ACCRETE. Such systems are characterized by:

- Small Rockballs through Inner and Habitable Zones.

- Often Super-Earths or Gas Dwarves between the Habitable Zone and the Frost Line.

- Two or three Gas Giants starting at the Frost Line, with the center of the three normally the most massive.

Figure 2: ACCRETE-type Systems

At the time Classic Traveller was written (Tech Level 7bis, late 1970s), the above were the only examples of solar systems; one actual data point (Sol), simulations which gave somewhat similar results (ACCRETE), and one sketchy astrometric analysis of a nearby red dwarf (Barnard’s Star). Inner-system Rockballs spaced out up to the Frost Line, outer-system Gas Giants beyond. Even hard-SF worldbuilders of this period such as Poul Anderson followed this pattern.

Then at Tech Level 9 (early 2000s), we became able to detect exoplanets in other systems – Doppler-effect gravitational perturbations from orbiting planets and the occasional transit. And discovered the hard way that…

“…the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose. “

– J.B.S.Haldane, 1927

Red-hot Jupiters in sun-grazing torch orbits. System after system after system that could fit within the orbit of Mercury with room to spare. Wildly-eccentric orbits from Torch Orbit perihelion to Kuyper Belt aphelion. Planets around neutron stars and white dwarves. Planets whose mass dwarfed Jupiter. Brown Dwarves, intermediate between Gas Giants and red dwarf stars. Everything except what we thought were “conventional systems” like Sol and the ACCRETE runs.

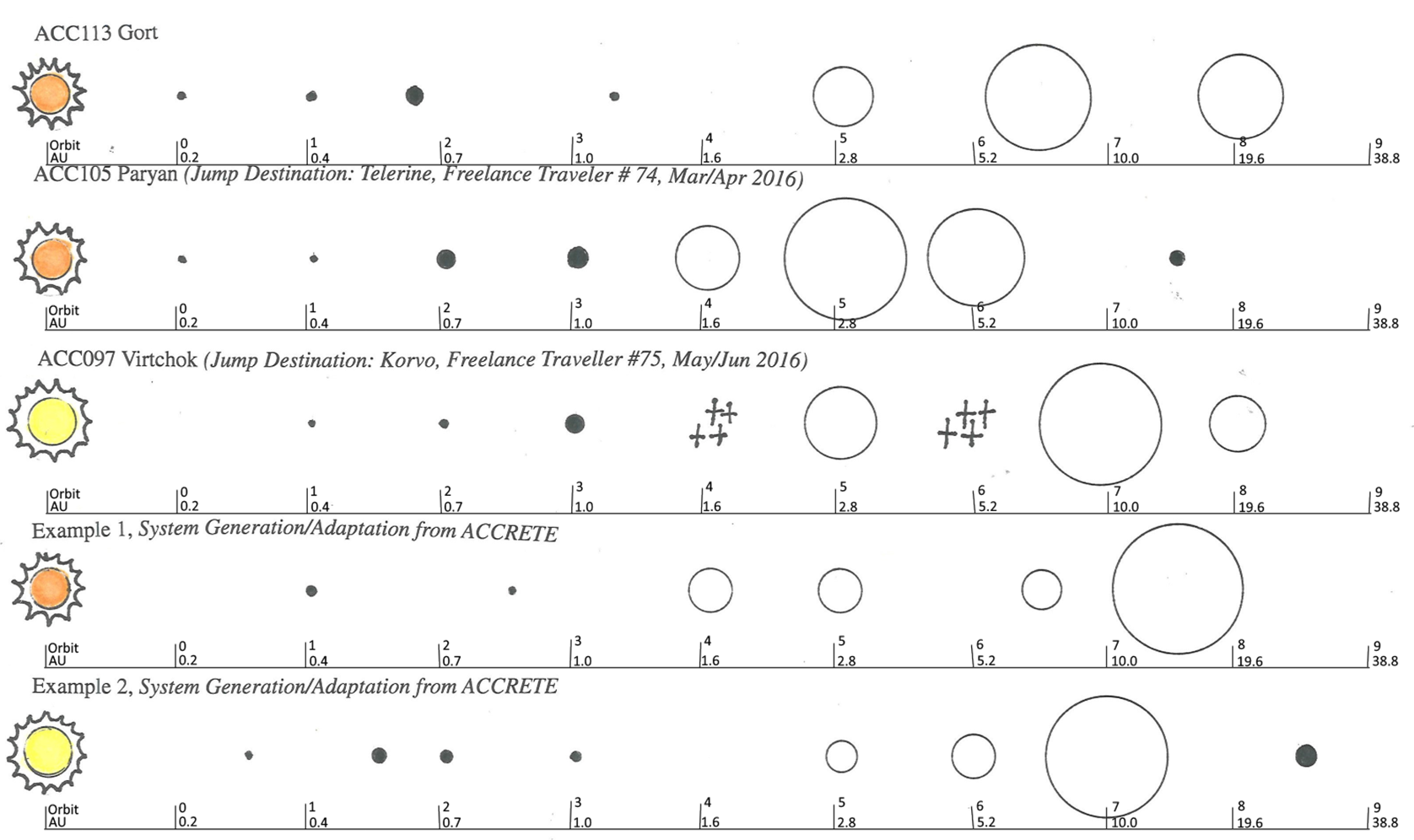

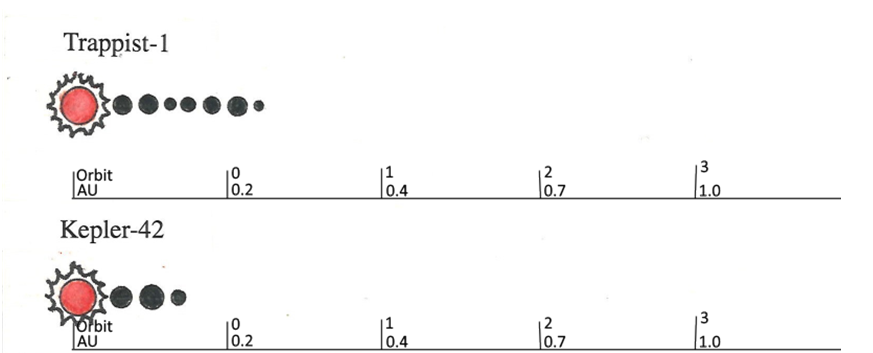

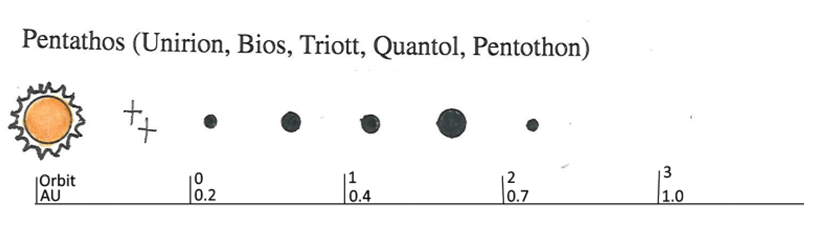

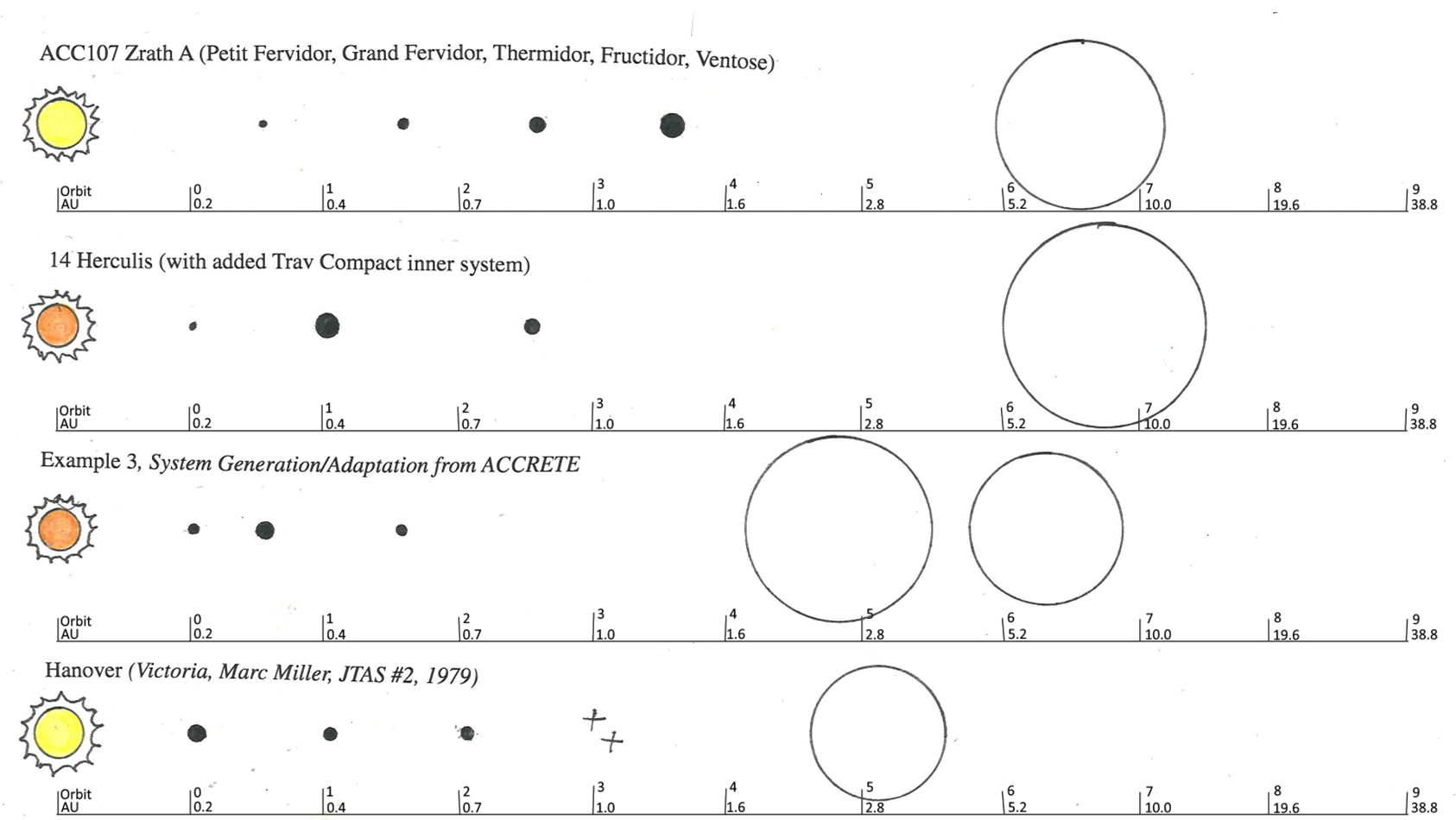

Compact Systems have all of their planets crammed together in Close Orbits well inside Orbit Zone 0. Resembles a Gas Giant and its moons more than a solar system; planets will often be in an Orbital Resonance similar to the moons of Jupiter. This is one of the more common types of discovered exo-systems.

Figure 3: Compact* Systems

“Traveller Compact” Systems are Compact systems adapted for Traveller by being slightly “stretched out” to fit Traveller orbital zones (Close, 0, 0bis, 1, 1bis, 2...)

Figure 4: Traveller Compact Systems

Dusty Systems have multiple asteroid belts and/or dust disk(s) outside of planets (e.g., Kuiper Belt or Oort Cloud); this often (but not always) indicates a young system.

Figure 5: Dusty Systems

In Failed Binary Systems the entire outer system consists of a single Very Large Gas Giant (VLGG) or Brown Dwarf whose gravity well has swept up everything except a small Compact or Trav Compact system hugging the sun.

- A VLGG is defined as over 600 Earth-masses (“Double Jupiter”), the point where surface gravity (5+ gees) makes fuel-skimming impossible.

- A VLGG in a low-eccentricity orbit will clear out two Orbits inward and one outward;

- A VLGG in a high-eccentricity orbit can clear two Orbits inward measured from its perihelion (minimum Orbit) and one outward from its aphelion (maximum Orbit).

- Result: A big empty gap between the VLGG and whatever inner system remains. Any planets that would have formed in the gap (including any other GGs) are merged with the VLGG, further increasing its size/mass.

- The VLGG could be a place of interest in and of itself: a miniature compact system with spectacular rings, several large moons (possibly larger than some of the inner planets), and a “mini-asteroid belt” of dozens to hundreds of dwarf moons.

- Some Real-Life Failed Binary systems (such as 14 Herculis) have more than one VLGG in the outer system (a Failed Trinary?), but the effects on the inner system orbits remain the same.

- Some Real-Life red dwarf systems are Failed Binaries in miniature, with one or two planets (usually Super-Venuses) in Close orbits and a Gas Dwarf or SGG in one of the numbered Orbits with a “dead zone” gap in-between.

Figure 6: Failed Binary Systems

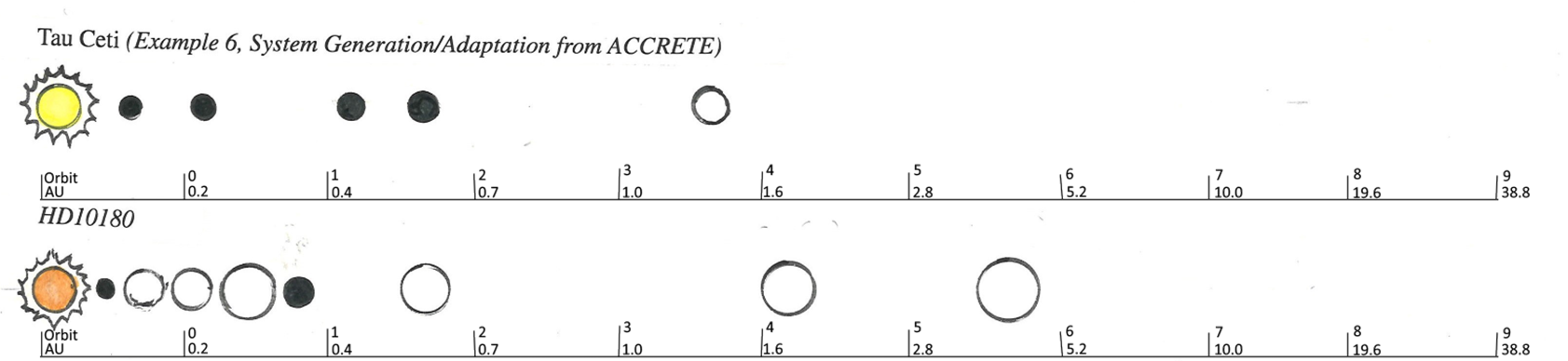

Frost Line Systems consist of several Super-Earths, Gas Dwarves, and/or SGGs extending out only to around the Frost Line.

Figure 7: Frost Line Systems

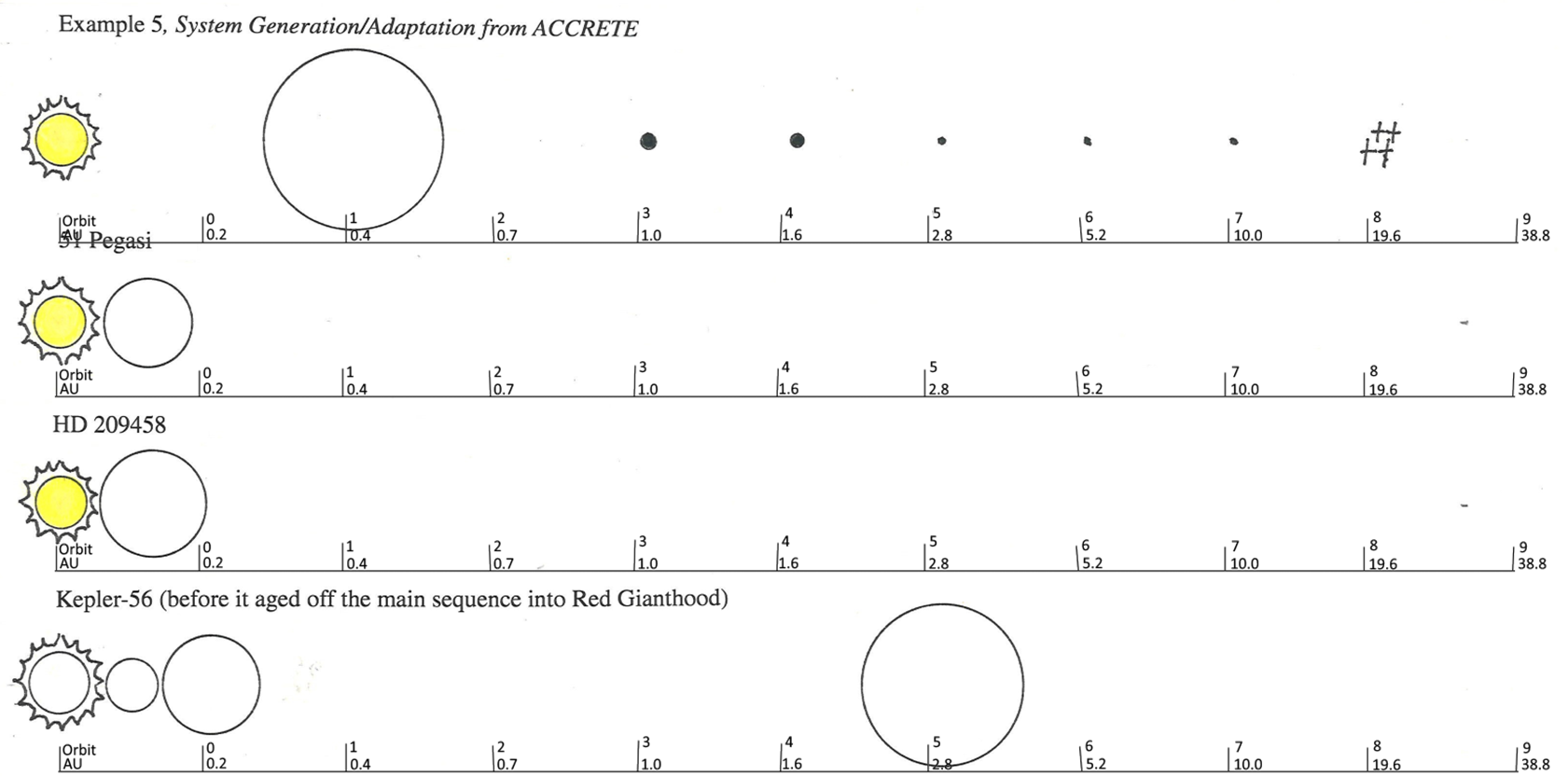

Hot Jupiter Systems generally have a Gas Giant (usually an LGG or VLGG) in an Inner Zone “torch orbit” (Close Orbital Zone), possibly others farther out (but with empty-orbital zone gaps between). This is the easiest type of system to detect over interstellar distances.

There might be some small planets outward of the Red-Hot Jupiter, but they would be small and far between; the migration of the Gas Giant in from the Frost Line to the sun would have swept up or thrown out most of the protoplanetary disk material.

Some Real-Life Hot Jupiter systems (such as 55 Cancri or Kepler-56) have an additional Gas Giant that remained at or beyond the Frost Line, forming a hybrid Hot Jupiter/Failed Binary system.

Figure 8: Hot Jupiter Systems

Binary/Multiple Systems:

Between a third and a fifth of star systems are binary “double stars” or multiples (three or more); the proportion rising as the stars become more massive.

| Percentage of Systems with Double Stars | |||

| Spectral Class | Close Binary | Wide Binary | Total |

| F (yellow-white) | 7% | 6% | 13% |

| G (yellow dwarf) | 6% | 9% | 15% |

| K (orange dwarf) | 4% | 2% | 8% |

| M (red dwarf) | 6% | 2% | 8% |

| Brown Dwarves | No information; assume same as red dwarves | ||

| Information in this table is from Habitable Planets for Man, Stephen H. Dole, 1964, p96 Note: When the two stars are of different spectral classes, go with the larger (i.e., higher on this table) |

|||

A Close Binary has the two stars orbiting each other at a distance of Traveller Orbit 1 or less (usually Orbit 0 or Close) in a low-eccentricity (near-circular) orbit.

In a Wide Binary the separation averages 18 to 26 AU (Traveller Orbit 8 to 9) with an eccentricity averaging 0.5 (1½ Traveller Orbits between perihelion and aphelion distances).

Note: Some sources place the percentage of binary/multiple systems as low as 10%, some as high as over 30%. This “Old School” article goes with the best Old School information available when Traveller first hit the gaming scene in 1977: The lowball figures of Dole’s 1964 Habitable Planets for Man. For highball figures, triple the percentages; for middle-of-the-road figures, double them.

Binaries/multiples tend to have fewer and/or smaller planets, as the multiple suns have swept up more of the protoplanetary disk that would have accreted into planets. Also, most binary companions are in eccentric orbits, further increasing the amount of material swept up or thrown out-of-system by the duelling gravity wells. In Real Life, the maximum stable orbit for a planet that orbits one sun (“S-type orbit”) is ⅕ the minimum separation between the two suns. For a planet orbiting both suns (“P-type orbit”), five times the maximum separation. Note that intermediate companion orbits could clear out all planetary orbit zones between the two, leaving no planets insystem.

In Book 6: Scouts, a binary companion clears out all Traveller Orbits inward down to half the companion’s orbit and two Traveller Orbits outward. Factoring in the eccentric orbits of most companions, measure the inward results from the perihelion (minimum separation/orbit) and the outward results from the aphelion (maximum separation/orbit).

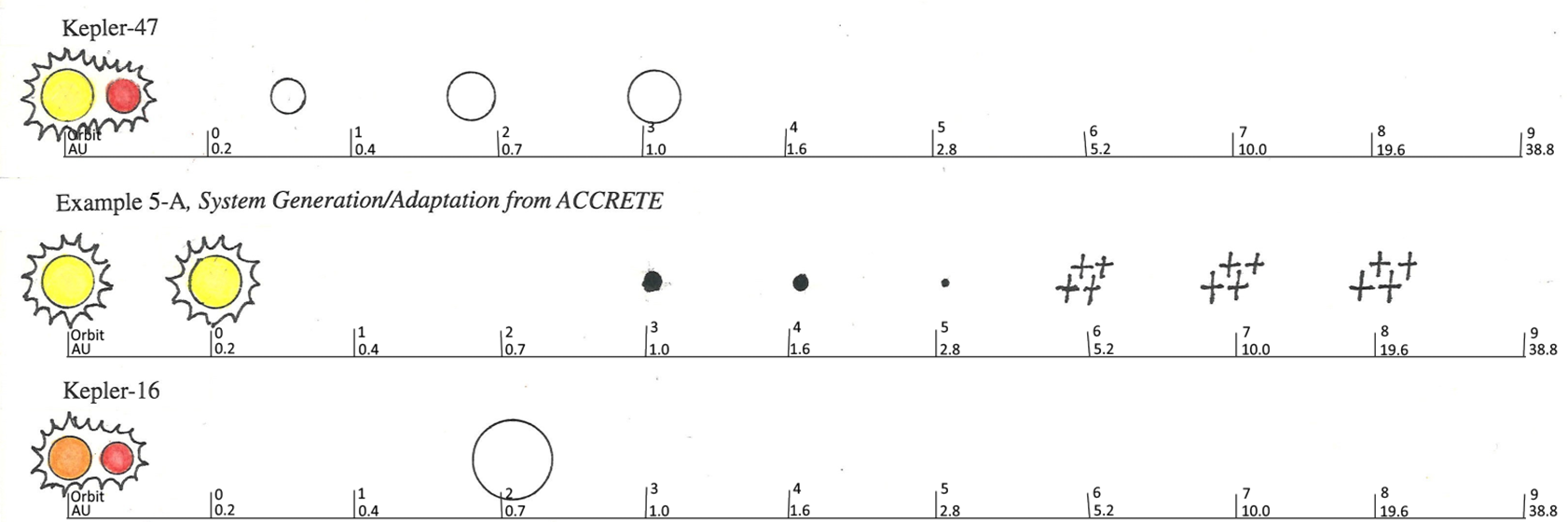

P-Type Binary Systems are those where the two stars are close together and all the planets orbit the pair; all planetary systems of Close Binaries will be of this type. The twin suns’ orbit around each other tends to be low- or zero-eccentricity; destabilizing orbital resonances between the suns create gaps in the planetary orbits and any asteroid belts. (These systems may also be called “Tatooine Systems”.)

The sky picture from a mainworld insystem would be familiar to anyone who’s seen the original Star Wars movie – a double sun, merging and separating as they orbit each other. If the two suns are different in size and spectral class/color (such as Kepler-16 and Kepler-47), a small redder second sun visibly orbiting the main sun.

According to Book 6: Scouts, the minimum planetary Orbit in such a system must be at least two Orbits beyond that of the secondary sun; anything closer in is swept clear by the dueling stellar gravity wells. The suns in such a system are usually in low-eccentricity (near-circular) orbits around each other.

Figure 9: P-type Binary Systems

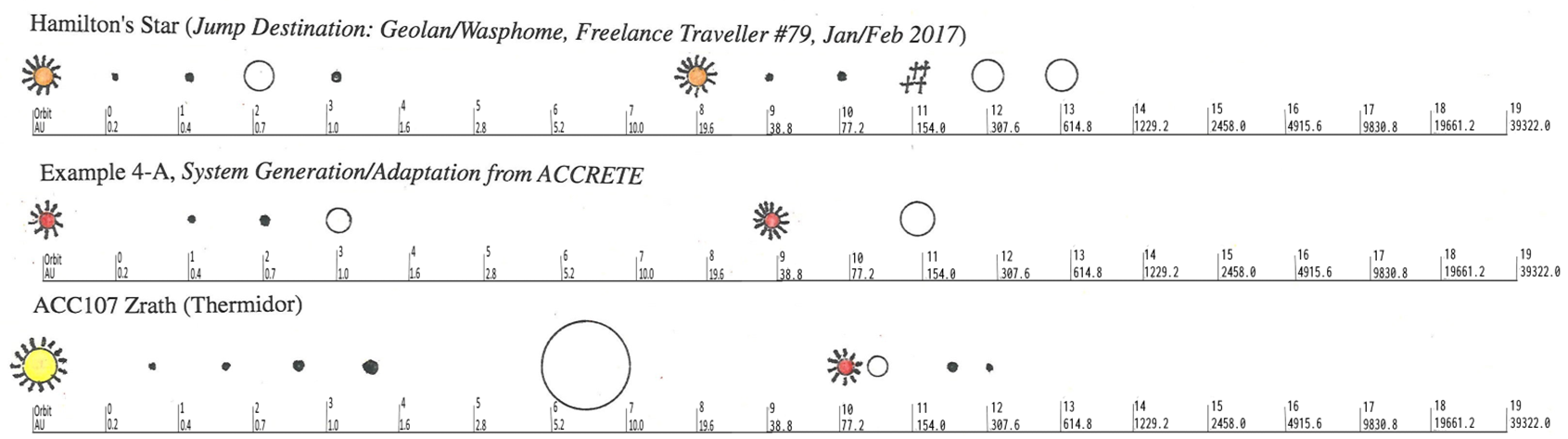

S-Type Binary Systems are Wide Binary systems with planets orbiting one star or the other – effectively two planetary systems in one. Each stellar component can have its own system with its own mainworld – two mainworlds for the price of one. Might take a week to get from one to the other with a “Jump-0” or a couple weeks with a burn/turn/burn, but it doubles the number of Jump Destinations in a hex.

According to Book 6: Scouts, the maximum planetary Orbit for each star in such a system is half the stellar Orbit. As this type of binary tends to more eccentric stellar orbits, this maximum planetary Orbit should be measured from the minimum stellar Orbit.

If one star is noticeably larger than the other like an Mv (red dwarf) companion of a Gv (yellow dwarf) or Kv (orange dwarf), the “half the minimum stellar Orbit” can be adjusted up for the larger component and down for the smaller; larger stars have bigger gravity wells.

Figure 10: S-type Binary Systems

A Far Binary (like Alpha & Proxima Centauri or Fomalhaut B or C) is a super-wide binary. Though the two stars are still gravitationally-bound to each other, they are more like two stars flying in formation, separate enough that they do not interfere at all with each others' full-size planetary systems. In Traveller terms, they are effectively two systems sharing one subsector map hex.

In an S-type system, the sky picture from the mainworld is much less spectacular than for a P-type system. The Second Sun appears as a super-brilliant star, bright enough to cast two shadows during the day and illuminate the “night” in a cloudy-day level of light. Said suns will separate and conjoin as the planet orbits, giving the world a true night when both suns are down, a day with an extra light source when both suns are up, a conventional day when only the main sun it up, and a Second Sun dim daylight when only the Second Sun is up.

In a Far Binary, the Second Sun is even dimmer, Second Sun daylight might be only a twilight. A red dwarf Second Sun in a Far enough Orbit might even just appear as a extra-bright star, bathing the night is a ruddy “moonlight”, barely able to cast shadows.

Customizing Systems: Mix and Match

Scouts, ACCRETE, and RL systems – solo, binary, and multiple – provide a variety of systems for a subsector. For further variety, they can be hybridized and customized:

- Got a Real-Life system like 14 Herculis or Epsilon Eridani with Gas Giants in decent orbits and no known other planets? Add a Traveller Compact inner system for your mainworld.

- Two Real-Life systems, one with a compact or frost line system (like Tau Ceti) and one with only an outer system (like Epsilon Eridani)? Combine the two with one’s inner system and the other’s outer system.

- An ACCRETE system whose outermost planet(s) are outside the maximum orbit?

- Make them moons of the biggest Gas Giants.

- Use them to fill in orbital zones in the inner system, like an Orbit Close or 0 Super-Earth. Some Real-Life systems even have a “debris field” inside their innermost planet, like a Close Orbit asteroid belt or planetary ring.

- Break the ACCRETE system at or outward of the largest Gas Giant, give it a red dwarf companion in a decently-far orbit (far enough so as not to disrupt the system), and use the planets outside the breakpoint for the companion’s compact system.

- Or any combination of the above.

- Combine either type of Binary with a Failed Binary VLGG for a Failed Trinary.

- A Failed Binary whose VLGG has cleared out all the good planetary orbits? Make one of its moons the system’s mainworld. (Beware of Van Allen Belts!)

- Compact/Traveller Compact system with no LGGs? Add an “asteroid/dust disk” outside the planets for a hybrid Dusty system. (And spectacular zodiacal light effect in the mainworld’s night sky.)

- An ACCRETE system whose major GG approximates that of a Real-Life system (such as System Generation/Adaptation from ACCRETE Example 2 and Epsilon Indi A)? Congrats! You now have an inner system for that Real-Life system!

- Create a Far Binary from two systems (generated by any method) by binding the two systems together with a minimum separation of at least twice the Traveller Orbit of the systems’ farthest planetary Orbit – two systems for the price of one!

- A Far Binary civilization with space travel but not Jump Drive still has its own two-system Pocket Empire, with all that entails. Just instead of a week between systems, it’s more like a month or three travelling Low Passage in “sleeper ships”.

- A hybrid Trinary system consisting of a Close Binary with a P-type System and a Wide companion with an S-type system. The P-type can either be the brighter or dimmer component.

- Or a Trinary like Alpha Centauri consisting of a Wide Binary with a Far Binary companion, all S-type systems – three systems for the price of one!

Applying all the above should give a subsector a wide variety of unique systems, many with their own insystem exploration/adventure paths beyond the mainworld on the subsector map. Entire systems to explore, above and beyond Downport, Startown, Central City, and Outback.

Freelance Traveller

Freelance Traveller