Antinet/Zettelkasten for Traveller Writing

You may have noticed a slight uptick in my writing output since the start of the year. I should check my submissions spreadsheet to see if it’s actually measurable, but it certainly seems apparent in my social media posts.

There is a reason for this. It’s not just because of a decision last year, inspired by a friend, to try posting something on Facebook daily. Initially I had thought I’d just be posting snippets such as newly arrived books, recently added entries to the bibliography, or resurfacing old material just to bring it people’s attention again. Now I find that I’m more often than not including Traveller things I’ve ‘done’ in the day which may be too small or obscure to work up into an article for Freelance Traveller but still seem interesting or fun in some way.

You may not be familiar with a German sociologist called Niklas Luhmann (born in Luneberg, in 1927) who wrote some 460 academic articles and over 70 books in his 40-year career. He had 200 more articles in preparation in his estate when he died. I think most would agree that that’s an astonishing body of work. Now of course, he was producing scholarly, academic material of much more value than anything I do - although I hope I don’t write as obscurely. He seemed to think readers should have to fight to understand what he was talking about or it wasn’t worth the effort. I’ve read him in English translation and I don’t think it’s the translator’s fault that he’s hard work. I like to shoot for as readable as possible, even if I miss. Luhmann also barely edited his work which struck a chord with me as I’ve often moved on to the ‘next thing’ or can’t step back far enough to see the faults. It’s why I’m very grateful to Jeff and others who have the patience and skills to edit me.

When I heard about him, you can imagine that my ears pricked up as to just how he managed to have such a prodigious output. Apparently, it was because of his zettelkasten; a card index he had developed over 30 years, and which had some 18,000 cards or more at his death.

I came to him because I’d been looking into the concept of zettelkasten. I’m a keen reader and note taker but whatever ‘system’ I thought I had regarding my notes (commonplace books, filofax, text files, Google Keep notes), I only really ended up with physical notes that I couldn’t find and struggled to store or computer files that would get lost on hard drives or digitally degrade over time. I thought maybe a cloud-based system using Notion, Obsidian or similar might work better. I perhaps haven’t given Notion long enough, but it wasn’t jumping up and down at me as ‘the solution’.

For better or worse, early on in my investigation - working at a university I find it difficult to call a bit of googling ‘research’ - I came across Scott Scheper’s Antinet Zettelkasten. I was intrigued - he goes into some detail on Luhmann and vociferously promotes the advantages of the physical approach of noteslips. I had no intention of doing anything analogue, however. It would all be digital and I’d just take the method and apply it electronically. Hah! Apparently, I’m not alone in that and others have tried the same. In fact, Scheper can be a bit rude about such which is not my intention. If that’s what you prefer, go for it.

But Scheper does explain - at some length (he writes very readably if rather repetitively) but with some evidence - how an analogue approach is what made Luhmann’s system work and that digital zettelkasten don’t give the same results. Indeed, he coins the word ‘antinet’ to distinguish an analogue zettelkasten from the digital brethren which now rather overwhelm any searches on the subject. Not helped by Sönke Ahrens’ How to Take Smart Notes which is the dominant book on zettelkasten in Luhmann’s fashion, but which gets some of the most critical features wrong (as does Wikipedia).

Some of the advantages of an analogue system include:

- On physicality:

-

- research suggests that physical writing helps imprint the content on your brain (typing or worse still, copy/paste doesn’t have the same power), it forces you to dwell on the material

- physical writing encourages you to keep the ‘irresistible’ rather than just anything reducing the ‘noise’ of your system

- the physicality helps prompt more than just the content but also the moment, the materials you’re using, the thinking behind the thinking (this isn’t impossible with digital, but it’s much, much less likely)

- for those that like the physicality of pens and penmanship, it’s fun (this doesn’t grab me but the whole librariany bit of cards and their arrangement does)

- For creativity:

-

- it’s simple and has fewer distractions

- it can help slow down your mind and allow you to develop thoughts

- it can help unlock creative insights that would otherwise remain disconnected in disparate fields. Luhmann says the magic happens from “interactions that were never planned, never preconceived, or conceived by your current way of thinking”; the constraints actually help with this

- The system helps itself:

-

- deciding where in the system a note will go helps reinforce memory about what you have and where it is

- considering indexing terms reinforces memory and encourages you to keep to the main ideas rather than ‘everything’ (indeed, computer search is actually a ‘bug’ in digital zettelkasten because it can return too much and doesn’t require any thought at the time you create the note)

- reviewing nearby notes as you find the place for an idea, quote or reflection again helps with memory imprinting (the tree structure ends up introducing structured accidents that are otherwise impossible to replicate)

- it acts as a ruminant for your thinking and knowledge rather than the superficial knowledge of reading without notetaking, or notetaking and not reviewing/retrieving

- you’re much less likely to spend time fiddling with the system (i.e. the software or the display or reorganizing thoughts - the latter being fatal to memorization)

I’m not going to take 600 pages to convince you - and Jeff wouldn’t countenance it. I may not convince you at all. Who wants analogue these days in a time of computers, phones and clouds? And yet, my own experience with both digital and physical suggest that there’s something in the analogue approach and I’m giving it a year to see whether it works for me or not. Luhrmann said it takes several years to get ‘output’ from his system, Scheper says that with dedication and application to the process it can be helping you write in months. I happened - perhaps by good fortune - perhaps by really ‘going for it’ - to find it was helping after just weeks and indeed, my antinet has already produced a small book (not Traveller unfortunately) as well as several other things for church, work and hobby. The subtitle of his book gives you a clue: a knowledge system that will turn you into a prolific reader, researcher and writer.

If you just want to enjoy your reading, stop here. If you take notes from your reading (or watching or doomscrolling) and only want to refer to the notes if necessary, keep doing whatever you’re doing (physical or digital). But if you’d like your reading and notetaking to actively feed your writing and increase your output, then read on. I’ve spoken to friends in all three categories and can see that this isn’t for everyone, or even very many, but if that sounds like you, read on!

Scheper notes an antinet is useful for writers who wish to notate thoughts and ideas from their readings, “it’s mainly useful for non-fiction writers who do much reading, thinking and processing of ideas. The antinet develops thoughts both in the short term and the long term… the purpose of the antinet is to develop your thoughts so that they are more thoroughly evolved and supported by the time they make their way to your manuscript”.

Antinet

You can read Luhmann’s original journal article (in English) if you want, but I would have found it impossible to develop the system just from this. A couple of readings of Scheper took me through it, however, and got me going and I’ve not looked back since. I’ll see if I can summarize to spare you the tome that had to be shipped from the States, but it was worth buying and is now with a friend who is developing his own antinet.

Luhmann’s system had three parts:

- an index card set (you can hear the librarian in me getting interested already)

- a ‘bib ref’ - a card set of sources, possibly books, from which the main cards get their information and include notes of their own (the librarian drools)

- a ‘main ref’ set of cards that is the bulk of the antinet and contains all the thoughts, quotes and reflections that you want to include and which will feed into your writing (the librarian-cum-writer bounces up and down with excitement).

Let’s take them in that order as it starts with the easiest to understand. It happens to be the reverse order I keep the cards in my antinet but that’s purely my choice and it doesn’t matter at all if you want to have the index at the front.

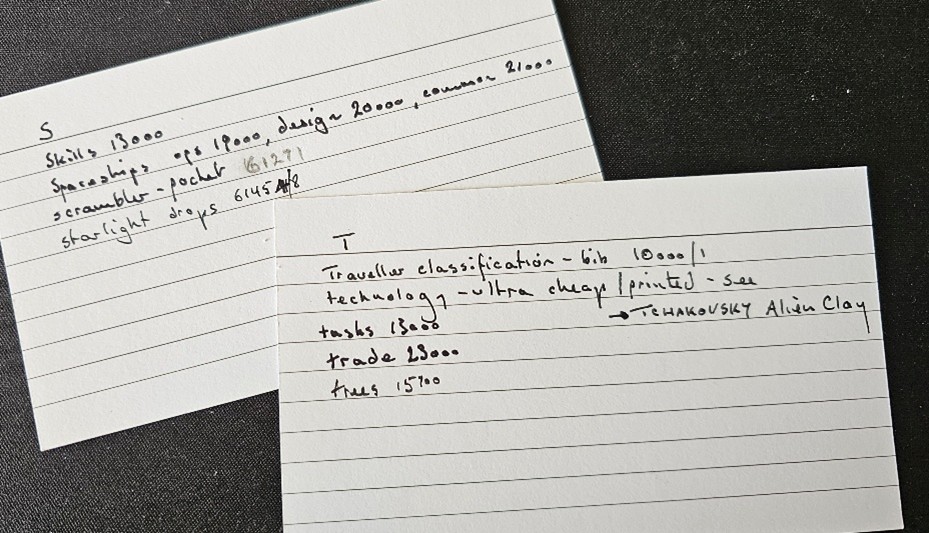

Index

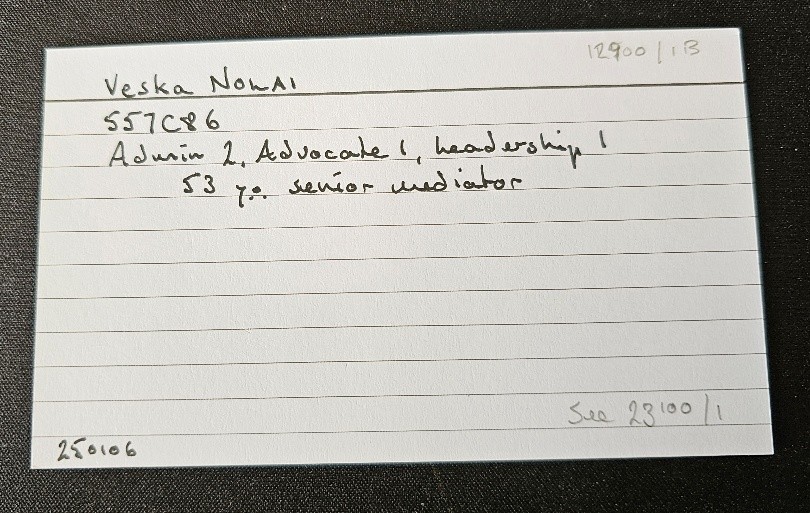

The index is a set of, initially, 26 cards - one for each letter of the alphabet. Six months in some of my letters (‘S’ was the first) now have two or three cards. Here you collect ideas and topics by a keyword so you can retrieve them, although it’s not the only way of finding content. Each keyword will point to one or more numbers, which we will come to in a moment that refer you to the mainref cards. I also include some biographical cards for persons of interest; they simply sit behind the relevant letter in their own alphabetical order.

BibRef

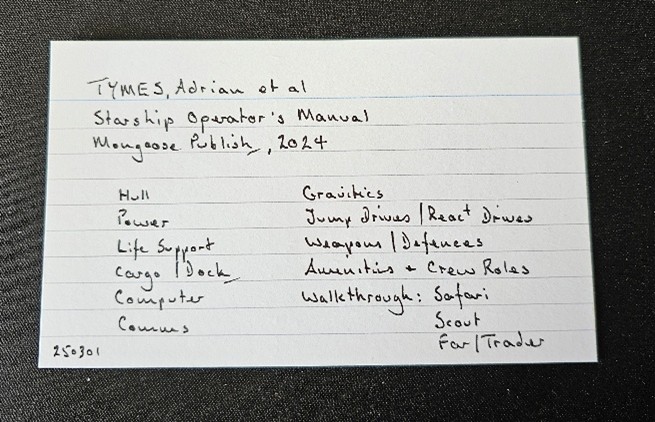

The bibref is also easy to understand. Any book that you read or film you watch can be represented by a card. It’s arranged by author but also includes title, publisher (director) and date such that you can produce a formal reference very easily. Obviously this is particularly important for an academic but can be helpful for general use as well. You can perhaps imagine that this was not a problem for me to get into. I have to teach referencing to students, so I was ready to go on that. Scheper suggests also including a goal for reading the book and I’m trying this but haven’t quite seen the value yet. Apparently, it helps keep you focussed on what’s important. Also on the front of the card is a note of the contents of the book. This might be the contents page reproduced if it’s helpful (and not too large), it might be a summary of the contents, or it might just be highlights. I find this depends on the book and what use I think I might be making of it in the future.

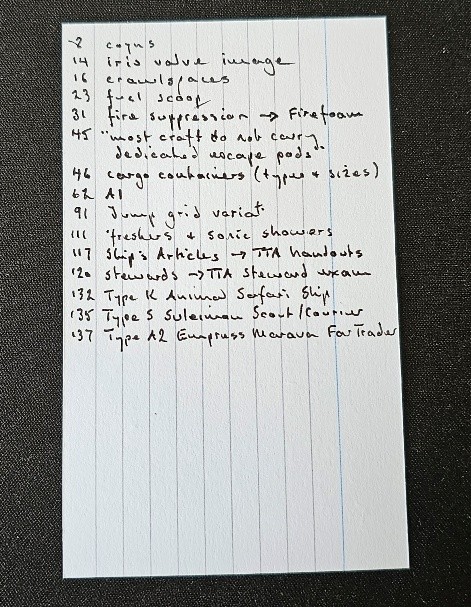

Then on the back of the card, which can act as a bookmark while you read the book, goes the notes you make as you read. Scheper follows Luhrmann and has the note and the page number. I find it’s neater and easier to read/find if I put the page numbers first and then the note.

Two things about your notes: this will not be everything you might jot down about a book. A quote will more likely (unless it’s very short) go on a mainref card, a reflection on something almost certainly will go on a mainref card. The notes on the bibref card will be very brief and not just what seems interesting (use the mainref card for those) but thoughts or points which really seem outstanding. Scheper suggests the word “irresistible”. Two reasons for that: firstly room on the card is limited and secondly this is acting more as an aide memoire to the book rather than detailed notes. Also, the idea isn’t to slow down your reading until it becomes a labour. Indeed, the opposite is true, Luhrmann seemed to be able to consume texts at a prodigious rate and I’m finding that the intentionality and discipline has made for a marked uptick in what I can manage to consume.

As a slight wrinkle, I also put into this sequence of cards definitions of words that are new to me or have new meanings I wasn’t previously aware of. I’m not entirely sure this is the ‘right’ place and they could easily go in their own sequence (perhaps they will when I have enough of them) or in the index. But I like them here and I’d suggest that it’s important to make your antinet your own and to make it work for you. Indeed, I have a suspicion that no one else would find my antinet useful just as I’d probably struggle to utilize someone else’s. In essence, you’re building a second mind, but it’s your mind.

You might also have spotted the reference to ‘bookmark’. What if you’re reading an ebook? Well, you can still keep the card to hand, but yes, that isn’t quite as easy to manage unless you have an ebook reader with a cover that includes a pocket or some such. Scheper would argue, with some evidence, that it’s the physicality of a print book and handling it and working through it that aids our memory and allows faster reading/processing. My experience would tend to support this. So, where I can, I’ll read print for preference, but I live in a world of ebooks, can’t always get the print version and so I’m still including ebooks. I am however noting them so I can perhaps determine later how much (poorer?) the experience is as far as the antinet utility goes. We’ll see.

MainRef

Finally, the mainref. This is where it all happens and is also where the analogue comes into its own versus digital zettelkasten.

First up you need a bit of structure. Completely random and you’re putting in more effort than getting out of it; too structured and you reduce the chances of generating breakthrough ideas. Scheper recommends half a dozen to a dozen top headings. Luhmann started with 118 categories initially but reduced this to just 11 in his mark 2 zettelkasten. I decided I’d use the ten top Dewey Decimal Classification categories, but you can use whatever system you like or invent your own if you’re doing something specialist. A friend involved with Regency history writing, clearly needed something tailor-made for his particular use. Alert readers will guess that it was out of this that I started developing my Traveller classification scheme, but you do not need such detail for an antinet. You are not trying to create an entire formal knowledge system. Indeed, the antinet is supposed to create a tree structure where every leaf is of the same value, not a hierarchical system. The main rule is that new cards simply go next to the ‘most similar’ card in the system.

The top categories will have numbers (you could use letters if you prefer) and then you simply subdivide the numbers as you see fit as you add content. You won’t be surprised to hear that I cheated a little bit in that I actually adopted the next level down of Dewey numbers as well. Partly because I’m a librarian, so why not; partly because I work with Dewey professionally so it’s helpful to reinforce my knowledge of the numbers for when I’m helping students; and partly because I knew my reading habits are very eclectic so that I was likely to be including ideas from pretty much every domain of knowledge. (We’ll come to Traveller later). Indeed, one of the criticisms of Dewey is the large space it gives to Christianity, but this was an advantage in my eyes as I was likely to be including a fair bit on this subject from devotional time, sermon notes and reading. Unsurprisingly, after six months, that section is easily the largest of my (non-Traveller) antinet.

So, you’re reading/watching/listening to something and come across an irresistible thought or quote. You want to make a note of that for the future, or you know that it will feed into a writing project you’re working on (or might work on). You can browse through the mainref to see roughly where it might fit, see if you have anything similar, decide whether you will indeed add it or not and assign it a number. Then you can write the card.

I add a date in the bottom left. It’s not a necessity and at present everything is too new for it to be of much interest, but I suspect that as time goes on it will not be uninteresting to know what vintage a card is. (I recall working at the Royal Geographical Society library which still at that time had a card catalogue. I could often get a good idea of what a book might look like, or which store it might be in from the handwriting or typewritten style on the card, the patina of the card itself and other clues.) One important thing is not to use the date as a title or index to the card (some digital tools do this). This prevents the tree structure from working.

You can add any reflections on the thought now, or at another time when revisiting the card. Such annotations can prompt recollection of more than just the words they contain. Your antinet is on its way to becoming not a second brain so much (a digital storage system will do that), but a second mind. One you can communicate with say Luhmann and Scheper - although this may take some time to develop so I’m only barely beginning to see this.

Two other things you might add to a card are hoplinks and xrefs. The former are simply links on a card to other cards which say something like “for more on x, see yyyy”. An xref is an external reference to a source outside the antinet (which may or may not be something that’s in the bibref as desired).

Once you’ve written a card, which might be a note on the text, a quote, or a reflection (or a mixture) and you’ve assigned it a number you can add index entries as you wish so that you can find that particular idea again directly. (Although it’s possible to find it by browsing through the mainref by the relevant concept if you wish). It’s best not to add too many index entries here, but just the main thought or possibly two. Luhmann used keyterms very sparingly as it encouraged him to explore his slips organically. One of the advantages of an antinet over a digital solution is that it doesn’t give you absolutely everything stored for a particular concept, but just the main ones. That can be rather overwhelming. It’s certainly possible to over-tag digitally. The cost of retrieval can outweigh the relevance. Particularly given you’re writing this all by hand, only using one or two keyterms reduces strain and time taken in producing the index entries. Once that’s done you can file the card. (Note to self: be careful not to file the index card in the mainref - or vice versa!)

A variant type of card is a collective. I call them collections because that matches with my bullet journal habit which an antinet can mesh with rather well. A branch collective (or collection) is a card at the beginning of a big branch in the antinet. For example, the ten top Dewey classes for me, but it may be further down in the scheme where some part of it has grown large. It effectively acts as an outline contents for that section. An outline collective is similar but is like a table of contents for a particular project (book, article, etc.) and groups logical content in a branch of your antinet. This is where your antinet can really begin to shine and my outline collective for my first book it produced became the table of contents for Atomic Prayer and guided me through writing each section.

It’s worth pointing out here that it is this browsing through the mainref, actively deciding on a place (nearest similar) and a number, writing the card, indexing it and filing it, that is what is so helpful in imprinting the idea or the quote or your reflection in your brain. It’s all too easy in a digital system to cut and paste from a source, let the software do the indexing and have no thought at all for how the thing fits into your system before moving on to the next thing. Yes, it’s quicker electronically; yes, it takes up less space on your desk; yes, it’s more transportable; but it is nowhere near as effective at becoming part of your second mind and then feeding into your output. Brilliant at storage; much less effective at creation. Laziness is not an option, you must create the links at the time or you’ll never find the thought again.

Scheper has an interesting quote here: “The Antinet allows you to experience the power of exploration. It promotes a way of exploring that is curious, deliberate, and that operates within a general and rough context. This is akin to the experience of being in a library and exploring shelved books.” Naturally, I’m sold!

While I think about it, another key aid in this retention is to use the material you’re adding. Whether in conversations, teaching or writing, the more that you can ‘output’ your notes, the more your memory is aided. Colleagues have noted that my tea break conversations of late have become both more wide-ranging and better evidenced although I do try to rein in some of my enthusiasm for an arcane something-or-other if the moment isn’t right! The astute reader will also see that writing this article is part of the reinforcement of my knowledge about antinets and I’ve rarely had to look up a detail in all the above to include it here.

At first, of course, your mainref will be small and for a while just a repository which can almost certainly be better replicated electronically. As it develops, however, it begins to ‘speak’ as both Luhmann and Scheper would say. Browsing to find one thing, you’ll stumble across something else which is most likely related and will reinforce your knowledge and feed into your writing. You’ll see connections you might have not noticed otherwise. You’ll have at your fingertips the details and references that will speed your writing process. This is still in its early stages for me, just starting out, but I’ve had glimpses of it already and it’s a powerful incentive to keep on with my year long trial. (To be honest, I’m pretty sure this has now become a habit that I’ll continue long after the trial). The accidental discovery of serendipity can be powerfulThis is one reason I vastly prefer a proper Roget’s Thesaurus to an alphabetical one. The ‘right’ word may not be in the item you look up but in a nearby section. Roget classifies its words so that similar concepts are in the same vicinity. The price of the extra lookup (from index to main entry) is worth it..

Just one example came while writing the book I mentioned above. In one chapter I realized that I needed some examples of ‘change’ in my lifetime. Previously I’d have had to stop writing, cast about in my memory or on the internet for examples that might work and probably got lost down a rabbit hole of distraction on the way. On this occasion, I knew I had a card listing just such examples as I wanted, that I’d been collecting over the previous few weeks thinking that it might be useful (and wanting to note a particular change that had just happened). I could locate the card, extract what I wanted and move on all in the space of a minute or so. No distraction, no having to revisit half thoughts I might have already had but not made a note of, no having to dig through archives to find details and dates. I even had all the referencing already done.

Another contribution to the writing process is reading with more intentionality. Both in choosing what I read and in choosing what I make a note of. Both have fed into both the antinet directly and my ‘output’. Another example here is Traveller related and I’ve probably mentioned before. I was over at the University’s mock courtroom helping with some MSc Forensic Computing students’ assessment. A glossy brochure on Pupillage caught my eye. I picked it up out of interest and to see what law students face after graduation and soon realized the application for Traveller: a pre-career possibility to join the Core Rulebook’s University and Academy options. That led into developing some Inns of Court and a character. It wasn’t long, of course, before it occurred to me that there was no Advocate career. The skill exists which suggests that it might be useful but little is made of it and perhaps it doesn’t get the love it could have. That produced another character or two and then linked to some fiction I was writing. Well, you’ve seen the results (or will do at some point) in the pages of Freelance Traveller. Not quite an entire theme issue just from noticing and deciding to add something to my antinet, but as much as I’ve ever produced on one subject from one initial idea.

Some practicalities

You’re going to need cards. Lots of them. Especially at the start when it feels as if you’re burning through them like there’s no tomorrow. That does settle down after a while and I estimate that I now add perhaps a three a day to my antinet. On average. Sometimes it’s more, sometimes less. It will depend on what the day includes in terms of time and reading (or watching or scrolling). I started with a trip to a stationery shop and bought three packs of 100 cards, but decided if I was going to commit to it I might as well do a bulk order and found 1000 online relatively cheaply. I reckon that will last me a year. I got two sets of tabbed A-Z index cards while I was at it - for the index and bibref, but strictly they’re not necessary. They do give the thing a proper ‘library catalogue’ feel to it, so that pleases me. Blank tabbed cards can be useful for your top categories in the mainref as well, but again, they’re not absolutely necessary.

Slips

You may prefer not to use cards but slips of paper. Zettelkasten actually translates as ‘slip box’. They take up far less room (my rough measurements suggest that at the weight of paper I’m using, you can get nearly three times as many slips into the space as cards. This may become important if you think you’re likely to be doing this for many years. I’ve experimented with this and now have a mixture of card and slips. I don’t have much science as to what goes on paper not card, but it tends to be things that I think are more ephemeral and just being used for one immediate project. Not that I, currently, bin them afterward and such project. It only takes a few moments, with a good guillotine, to slice up A4 paper into the right size and there’s the advantage of a variety of colours which can be more expensive in colour. Scraps left over become bookmarks or notelets.

Size

Luhmann used a European size (A6 I think, if memory serves) which isn’t easy to buy in the UK. The equivalent would be 6”×4” cards and there’s a part of me that thinks I should have jumped this way. Scheper did and that is what he recommends. I opted for 5”×3” for a few reasons. Firstly, I actually already had 100 or so 5”×3” cards from way back when I lived in a community where we’d been encouraged to have a ‘toolkit’ of cards to help with speaking engagements. Now I think about it, it was a kind of antinet of its own with its categories and single ‘thoughts’ and so on. These now sit proudly right at the front of my antinet and already linking into and being linked to from the brand-new cards.

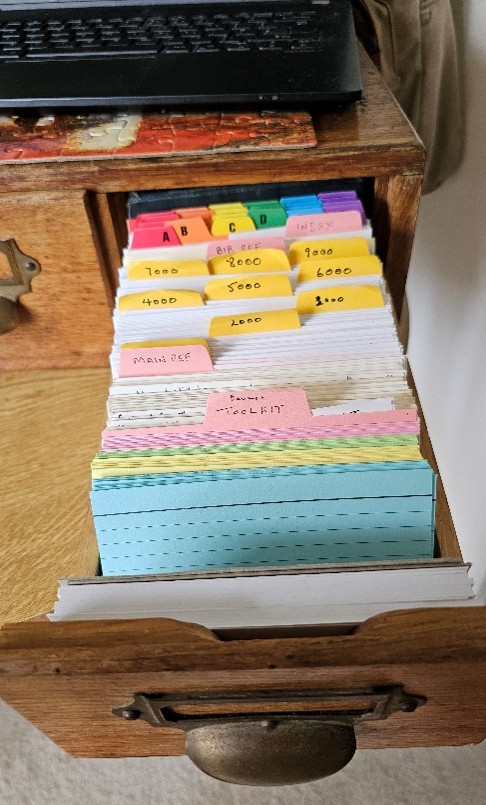

Secondly, I knew I didn’t have a lot of space in my home office. I have a set of maybe 150 6”×4” cards from my university days containing the first bibliography I ever produced as part of my degree. (On time travel as it happens.) I could immediately see how much larger an antinet containing hundreds of those cards would be. The third and final nail in the coffin for the choice was when I was asking around at work whether we had any old catalogue drawers still kicking around or destined for the bin. My boss just happened to have a two-drawer box in her shed which she kept seeds in. As I enthused about my purpose, she was happy to clean it out and bring it in for me to repurpose back to cards (the seeds could live in a bucket). It was designed for 5”×3” cards so that settled it. My Regency History friend has opted for 6”×4” - but he has more space. The downside of 5”×3” is less room for note taking - especially on the bibref cards, but this is probably a good thing for me as it forces more concision and a neater script. Neither of which I’m skilled at.

Storage

I lucked out finding a proper card box; nice new wooden ones are not cheap. (See photo at the top of the article.) I reckon what I have should take about 3000 cards and might last three years before I need to expand. We’ll see. It even acts as a laptop rest, replacing a Lego box that did the same thing but with less added purpose. So technically my drawers take up no additional room at all.

Pretty much any cardboard box that’s a sensible size will do or even a collapsible nylon storage bag/box I found online which is even lockable. Not that I need the latter feature but when my antinet had to travel with me for a few days to demonstrate to others, it was the perfect way of moving it. I started out with a simple wooden tray that had six ‘divisions’ and held perhaps 500 cards or so. Perfect to get going with. This still lives on my desk at work to hold a work version of my antinet which doesn’t grow as fast.

Writing Implements

Not much to say here except that you’ll want something you can write neatly with and that doesn’t put too much ink on the surface if you’re using paper slips - otherwise the reverse of the cards becomes hard to read. In fact, Scheper, or was it Luhmann, I forget which, recommend only using one side of a mainref slip or card. I’ve not gone that far.

Traveller

So far, you might think this is only relevant to Traveller in the abstract and it’s true that I started out quite intensely on my ‘real world’ antinet. But I knew from the outset I would want to be using the technique for Traveller and indeed, my main goal was to support Traveller writing. The non-Traveller book it produced first was a complete surprise to me.

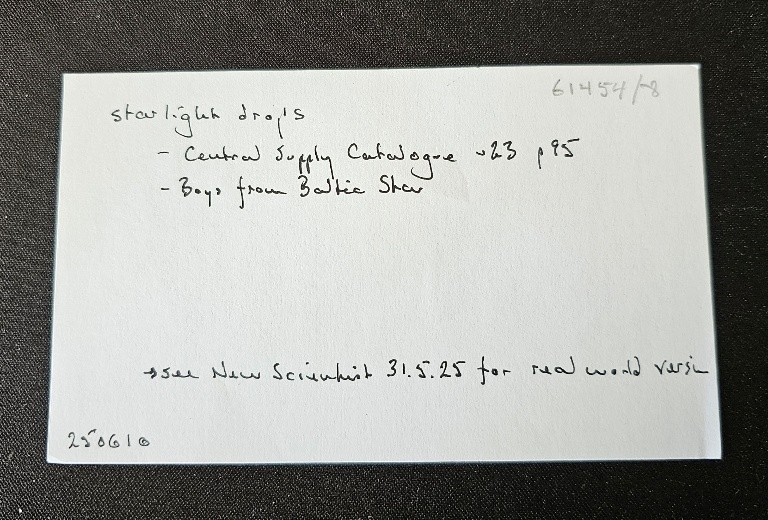

My first question was whether to do everything in one antinet or to develop two; one for the ‘real world’ and one for Traveller. I’m still not sure it’s the ‘right’ answer, but I’ve opted for the latter. YMMV, as they say. To distinguish the cards and systems, I decided that Traveller could have five-digit numbers where the other would have four-digit numbers. I’d keep them in the same card drawers though, one behind the other and cross reference freely. (So a note from a New Scientist article on, say, aeronutrition will link to something I’ve written for Traveller in its sequence; or the card for the pre-career Pupillage option mentioned above, gets a link to pupillage in the (admittedly small) law section in the other antinet. So far this is working, and I think it is wise to keep them separate, but I’m not sure it would have mattered. (I considered using different coloured cards in the same sequence but decided that would be confusing.)

I listed above some advantages of analogue; there are some cons of course:

- you cannot quickly search for keywords (but nor are you overwhelmed by irrelevant results)

- it takes a little more time to write than type (but this helps learning)

- there is limited space on a card (but this forces concision)

- it stamps your mistakes in time (but this can help subsequent thinking and navigation)

- you cannot share or publish notes as easily

- there is the risk of fire or water damage.

On the last two points, it can be argued that no one wants half-developed information anyway, so it’s better to publish work that has been processed and structured rather than just sharing a basic note or reflection that’s not been very well thought through. As for losing the antinet, much of the idea is to plant it more firmly in your own knowledge, so were it to happen, I’d just start again. And is something worth less if there isn’t a risk of loss? It’s a risk, but as Scheper says, it doesn’t keep me up at night.

One advantage might speak well to Traveller players is that of the playful mindset and antinet can develop. As role-players, gamers, we’re perhaps more attuned to that than, say academics might be (and yes, I’m aware there is a set of Traveller fans who are also academics), but there’s a spirit of playfulness, randomness and curiosity that is both fun in itself but also adds to the antinet.

For Traveller there’s also an interesting aspect of an antinet that I’m only just beginning to see. Because of the tree structure making all ‘leaves’ equal (rather than a hierarchy), something that initially seemed quite minor can come to much more prominence (and vice versa is true as well). An example of this was in a throwaway word I invented for a character description. ‘Firefome’ with the idea it was some SF foam that starships would employ to fight fires on board. It was worth noting but felt so minor I didn’t even put it on a card; a slip would do. However, it wasn’t long before I was digging out High Guard to remind myself what details were required for ship systems in terms of tonnage, cost and so on. That suggested a text box for the character description that included the mention of the word. But then I started wondering about what other systems there might be at different tech levels and slowly just a throwaway word became an entire article. Had I not been trying to be intentional about tracking creativity, I might well have just moved on with no more thought. Now you might argue that Traveller has managed for several decades without details on shipboard firefighting but I’d like to think I’ve remembered to keep the focus on role-playing and am not just inventing background detail that’s of limited use. Hopefully that makes it both of interest and use to other Referees.

In a similar vein, in thinking about where a card might sit and the categories I might use for its placement, it becomes easier to spot things that are not there and where there might be mileage in developing something for an adventure or writing an article on the subject. An example here might be in starports and seeing the ‘gap’ in descriptions of various elements of a ’port and inserting an entry for ‘energy supply’; or in diseases seeing the lack of what I’ve termed - with the help of a doctor friend - chronopathies. Perhaps you’ve never given consideration to a starport’s energy supply before but a recent outage at Heathrow shows just what gaming potential there might be in experiencing some form of disruption in transit, setting out to disrupt such a supply or aiming to fix the supply - probably under a time constraint!

It’s perhaps worth mentioning that with an analogue tool like this, mistakes can be tedious - either in the notes you’re making or the numbers you’re assigning (and don’t get me started on the untidiness of my handwriting). However, it’s useful to see this as an advantage and Scheper counsels not correcting anything but allowing the mistakes to stand. Luhmann certainly did. This is for two reasons: the first is that it can help with memory in that it gives texture to what you’re looking at and gives hooks which aid recall. More importantly, perhaps, it allows you to see your thinking at the time and to see how you might have changed or grown since then. Perhaps your number represents your thinking at the time but your knowledge has moved on; perhaps you’ve seen a better way of doing things. Yes, it can be messy; but this gives valuable insights in itself. You can imagine how I rebel against this and have to resist the temptation to replace a card or get the tippex out, but I’m learning to abandon any idea of perfection.

Scheper points out that you operate in two states whilst using an antinet. Firstly, in a ‘growth’ state - using your antinet to grow your own knowledge and understanding through reading and reformulation. Secondly, in a ‘contribution’ state when you’re using your antinet to write. You’ll oscillate between the two states but perhaps strive to be in the second as much as possible. I’ve found this is true as read Traveller material (or things that will inspire Traveller ideas) and then writing Traveller articles and the like. I’ll be reading and making notes as described above, then, when it comes to writing, I’ve notes, ideas, quotes, reflections and directions to take all at hand. I can’t say I generally suffer from that fear of the blank page (usually just switching domains or topics lets me get on with another project while the first something stews in the background), but I’m pretty sure working with my antinet has removed any fear of not knowing what to write next. Indeed, I have the opposite problem with too many ideas and too little time. I’ve put post-its on some cards which are works in progress but I must be careful not to simply fill the whole draw with such markers!

One advantage I didn’t mention above is that my antinet

is simply fun. The associative thinking, the surprise

connections, the internal dialogue - with your current mind

and your past self. As well as making reading and notetaking

more intentional, as well as producing results, there’s

a delight in generating cards, finding their home and feeling

you’re learning and being productive. That I can do this

to contribute to Traveller is a

bonus. Luhmann only installed cards in his system which were

related to publication requests he took on. I’ve decided

not to be that focussed, but I’ll report on whether

that’s a mistake at some point in the future.

An antinet can be the “purest, hardest, most time-intensive, but most rewarding way to develop your knowledge” (Scheper, p.41). Like Scheper I feared giving this a go would be a distraction or a “procrastination fuelled detour”; like him, I thought the idea of going analogue was absurd; but like he and Luhmann I’ve found that giving it a solid go has proved eye-opening. I can’t say that an antinet is going to be for everyone and perhaps not very many, but I would recommend reading - or at least skimming through - Scheper’s book and seeing what you can get out of it. It has interesting things to say on notetaking generally, analogue vs digital and is very easy to read. He’s not afraid to point out why an antinet may not be the right tool and he points out that the antinet isn’t the goal - the output is. He also references a fair bit of other reading which is useful and worth pursuing as well. I started doubtfully but have found both the process and the results far more enjoyable and productive than I had ever imagined so I’ve become both a believer and an evangelist, but try it for yourself and see if it’s helpful for your particular situation.

Notae propriae, notae

optimae.

Your own notes are the best notes.

Freelance

Traveller

Freelance

Traveller